I’ve been sitting in the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry for months as the only artist not using a computer to create art. I’ve deflected the numerous suggestions from the STUDIO folks to add computer power to my art by attaching my old mechanical sewing machine to a robotic arm. I also haven’t laser cut any fabric or created any Arduino-controlled blinky quilts. I still might do some of those things, but I’ve been having too much fun just spending time making quilts. The truth is also that although I am a computer science professor, computer programming is not actually a great love of mine. I can program, but I would rather supervise student programmers than do it myself.

I’ve also been doing a lot of improvisational work this year, trying to be more spontaneous in my art. Rather than pre-planning an entire quilt up front, I’ve been trying to design as I go. However, when I started working on the Interleave series I realized that some planning was going to be needed in order to develop quilts in which a third design emerges from interleaving two separate panels.

For Interleave #1 I did some paper prototyping with tape and scissors. For Interleave #3 I decided I wanted to play with creating curves from straight lines. I grabbed an image of a sine wave and pasted it into a powerpoint file and started drafting quilt designs from dozens of thin rectangular strips. Each design variation involved a tedious process. Golan Levin noticed what I was doing and suggested that I create the designs in a programming language called Processing. I mumbled something about not knowing Processing, and Golan offered to get me started. In about 10 minutes he had written a simple Processing program that drew sine waves filled with color that could be adjusted by dragging the mouse. He emailed me his code, expecting me to finish what he started.

It took me, the computer science professor, another five hours to finish what Golan, the art professor, had started. Golan is actually a much better programmer than I will ever be. But by the time I had finished I was hooked on Processing and could see the utility of writing code to produce a quilt design, even if I was ultimately going to use a traditional quilting process to make the quilt. I added lots of parameters to the program and implemented slider bars to control them — frequency, amplitude, offset, number of colors, etc. By fiddling with the slider bars I could try lots of design variants in a matter of minutes, and save copies of the designs I liked the best (annotated with the parameter values so they could be reproduced).

It took me, the computer science professor, another five hours to finish what Golan, the art professor, had started. Golan is actually a much better programmer than I will ever be. But by the time I had finished I was hooked on Processing and could see the utility of writing code to produce a quilt design, even if I was ultimately going to use a traditional quilting process to make the quilt. I added lots of parameters to the program and implemented slider bars to control them — frequency, amplitude, offset, number of colors, etc. By fiddling with the slider bars I could try lots of design variants in a matter of minutes, and save copies of the designs I liked the best (annotated with the parameter values so they could be reproduced).

I started out with nice symmetrical intertwining sine waves forming footballs, slender vases, and squat snake pots where the sine waves overlap. Then I discovered new shapes that could be created by offsetting the sine waves in each panel different amounts. These asymmetrical shapes, like flames in the wind, were even more intriguing and dynamic than the snake pots. So I experimented with asymmetric design variants and eventually settled on a design to render in fabric.

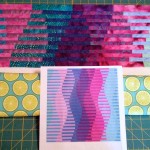

Next came fabric selection. I chose nine commercial batik fabrics and one shiny woven fabric from my stash. The visual texture of the batiks provides an added dimension beyond the flat solid-color image in the computer-generated design.

Next came fabric selection. I chose nine commercial batik fabrics and one shiny woven fabric from my stash. The visual texture of the batiks provides an added dimension beyond the flat solid-color image in the computer-generated design.

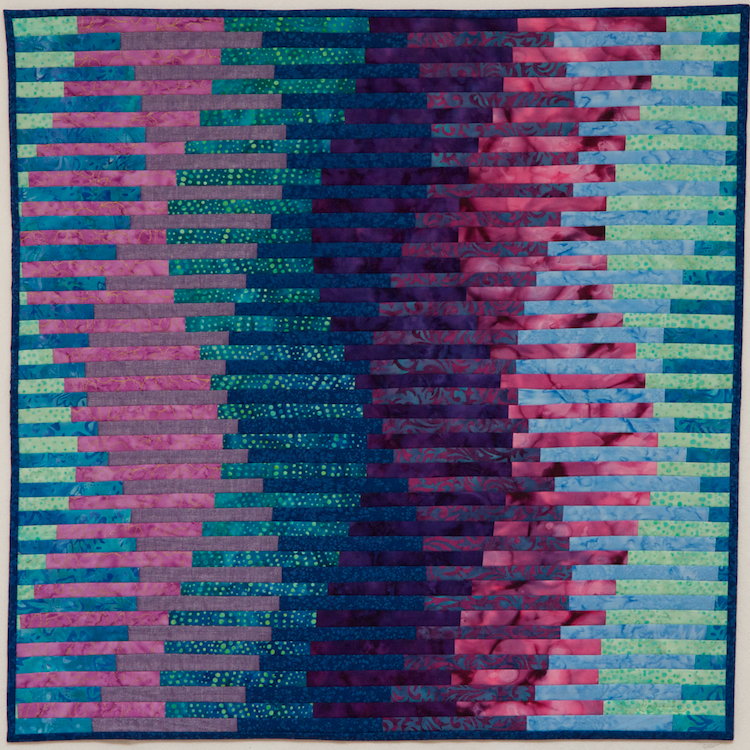

The next problem was figuring out how to construct this quilt. With two previous Interleave quilts under my belt, I was starting to get a feel for what techniques are most effective. However, this is the first quilt where I attempted interleaved curves. I considered piecing two panels with sine waves and slicing them — basically the process I used for the previous two Interleave quilts, but without any curves. But curved piecing can be tricky, and it occurred to me that this quilt could be created entirely from straight lines. My approach was to cut strips of fabric a little bigger than the width of the colored bands, and a little taller than the height of the quilt. I sewed them together into two tubes with five bands each. I then created a full-scale paper template for the sine waves and used it to cut open the tubes in a stair-step sine wave pattern. Then the tubes were ready for slicing into one-inch strips and sewing to the quilt batting and backing. This time I prepared the backing with half-inch marks, carefully aligned, to make it easier to align and sew the strips. I used Fairfield Soft Touch Cotton Batting as I had in Interleave #2.

With the backing properly marked, the sewing went fairly quickly. It was exciting to watch the design emerge one row at a time.

I think the end result is quite striking. My first foray into writing code to aid my design process was successful. I don’t think I will use this approach for every quilt from now on, but I am eager to try it with some other ideas on the Interleave theme.